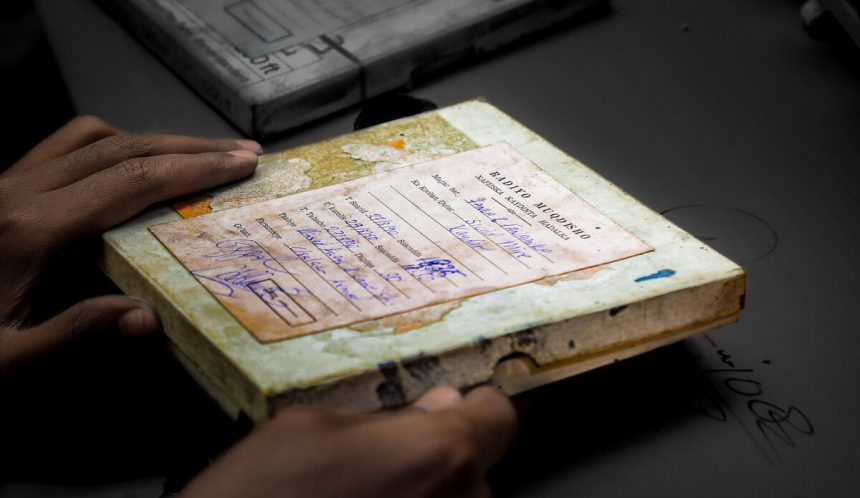

Mogadishu – Sitting in a small, windowless room in a government building in the Somali capital, Mohamed Yusuf Mohamed loops another audio tape onto the dilapidated machine and presses a few buttons.

After a few clicks, the antiquated device starts to whir and its wheels spin – one tape down, and another couple of hundred thousand or so to go.

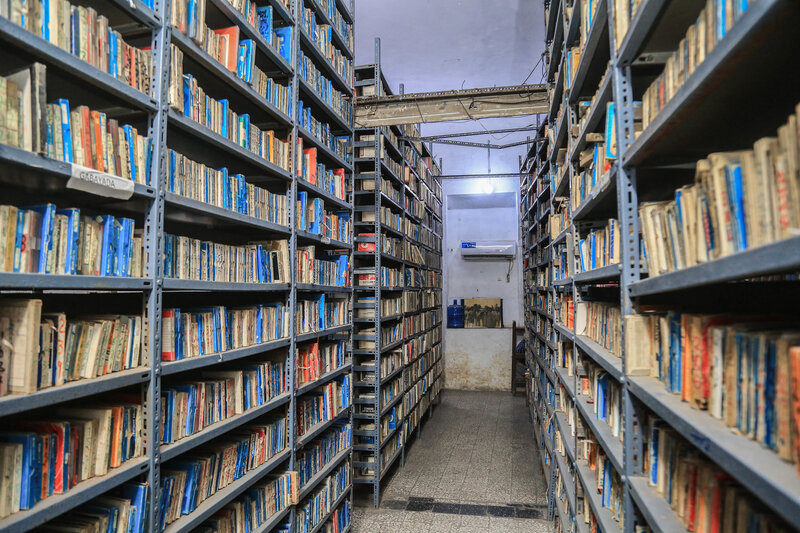

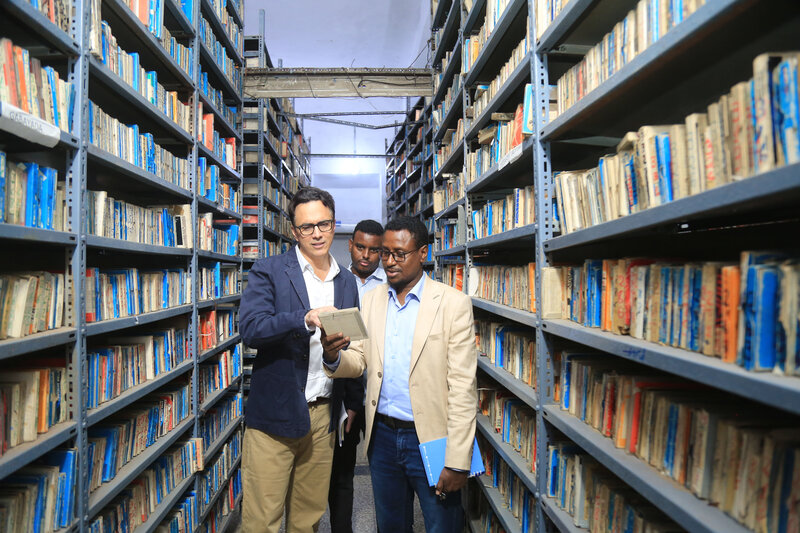

In the adjoining room, there are shelves more than three metres in height which teeter under a layer of dust and thousands of audio reels.

Given the decrepit equipment and limited staffing at hand, the project Mr. Mohamed and other colleagues are working on will take many decades to complete.

Their actions are part of a long-running effort to digitise some seven decades of unique historical recordings belonging to Radio Mogadishu.

“I arrive here at 8:00 a.m. and work until 4:00 p.m., digitising around 30 to 40 songs per day with very limited equipment,” he says.

Mr. Mohamed feels some pressure.

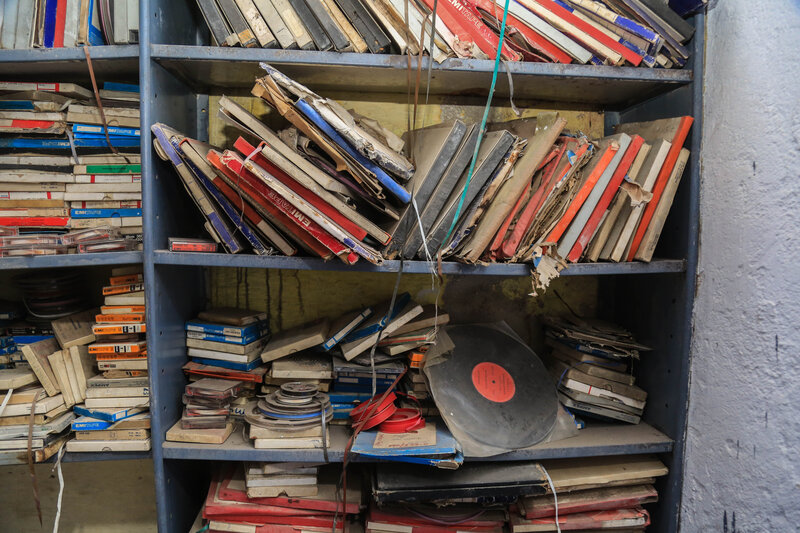

At stake are the only remaining audio recordings of much of Somalia’s history, with thousands of reels of music, poetry, religious texts, political speeches and drama shows stemming all the way back to the station’s creation. Much of it is in a poor state.

Nonetheless, Mr. Mohamed is conscious of the importance of his work.

“I feel fortunate to have the opportunity to participate in improving the history of my country,” he notes.

First broadcaster

Somalia gained independence on 1 July 1960, when the UN Trust territory of Somaliland – the former Italian Somaliland – and what was then British Somaliland united to form the Somali Republic.

Radio Mogadishu came into existence earlier. It was established in 1951, during the period when Somalia was held under the trusteeship of the United Nations and administered by its former colonial power, Italy.

It began broadcasting news in Italian, and Somali programming followed soon afterwards.

In the 1960s, Radio Mogadishu was modernised with assistance from the Soviet Union, and began broadcasting in Amharic and Oromo as well as Somali and Italian. In 1983, Radio Mogadishu’s sister organisation, Somali National Television (SNTV), was established.

War breaks out

This growth and progress of the national broadcaster came to a halt in 1991. Radio Mogadishu closed soon after the start of Somalia’s civil war, which followed the overthrow of then-President Siad Barre.

The station’s premises fell into the hands of warring factions. In 1993, the archives sustained some damage during clashes between one of the factions and international peacekeepers deployed in the city at the time.

The violence that engulfed the country led to the destruction of much of Somalia’s cultural heritage. Museums were stripped of their collections, with items destroyed or sold on the black market. SNTV’s archives were destroyed, and the material in Radio Mogadishu’s vaults was targeted.

As the civil war raged, there were various attempts to destroy or steal the vault’s contents. Only the courageous efforts of certain individuals hampered those attempts.

One of those individuals was Abshir Hashi Ali, then serving as a police colonel. In 1996, amidst the violence, he decided that he would protect the archives for future generations of Somalis.

“This site stores the history and data of Somalis… The archive was neglected, and there were many militias in the area. However, there were always good people from the local authorities who helped me to save this precious treasure,” Mr. Ali recalls.

“My aim was to protect this important heritage for the Somali people, wherever they are. My prior life as a police officer helped me to be resilient and to work for a long time in a place where I have no personal interest nor was I being paid a salary,” he adds.

Following the re-opening of Radio Mogadishu in 2001, Mr. Ali was made the station’s archives manager.

The majority of the 35,000 magnetic, reel-to-reel, tape recordings in the Radio Mogadishu archives – made up of Somali-language tapes, records and limited manuscripts – survived the war, although most of its foreign language collection was not so fortunate.

Following the re-opening in 2001, which occurred during the administration of Somalia’s then-Transitional National Government, the station operated from its original, small compound in central Mogadishu.

Its dedicated staff broadcast a range of programmes – news, music and talk shows – despite the threats and reality of violent retaliation from the Al-Shabaab terrorist group, which regularly fired mortars to silence the station.

Digital hopes

In the ensuing years, Radio Mogadishu has made further progress.

In the late 2000s, it launched a website of the same name, with news articles in Somali, Arabic and English. In 2021, the Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism (MoICT) – which oversees the national radio broadcaster – announced that Italian language programming would be recommenced thanks to support from the Italian government. The following year, the Chinese government funded building refurbishment and renovations.

But it remains a different story with saving Radio Mogadishu’s rich archives from further deterioration.

Reel-to-reel tapes are based on a long, narrow carrier tapes of various lengths comprised of acetate, polyester, or PVC; coated with a mixture of magnetic particles, often iron oxide fixed with a binding agent; and wound onto a plastic or aluminium reel of various sizes. This means that they are at risk of distortion and corruption – including breaking, stretching, delamination, demagnetisation, degradation because of overuse – and chemical changes in the binding agent, particularly through absorbing water vapour.

The MoICT has been trying to have the archival material preserved.

“This is the only archive for this nation after the civil war. As time passes, if we do not preserve it, it will only be seen in pictures,” notes Somalia’s federal Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, Daud Aweis.

His concerns are echoed by Radio Mogadishu’s director, Abdifatah Dahir Jeyte.

“Urgent action is imperative to safeguard the history, language, culture and literature of the Somali nation stored within these archives – considering the vastness of Radio Mogadishu’s archives, which contain more than 200,000 tapes, the digital conversion is currently incomplete, covering less than 30 per cent of the total content,” Mr. Jeyte says.

“We extend our warmest welcome to institutions and individuals willing to contribute to their digitalisation. This initiative is crucial for preserving the cultural and literary heritage of the Somali nation, which has been meticulously collected over the past half-century,” he adds. “Time is of the essence, given that in 2018, a portion of the archive was destroyed in a fire, resulting in the loss of some foreign language tapes.”

Initial attempts at digitisation began in 2013. With the support of the French government, African Union, United Nations and the MoICT, staff worked to preserve the collection and make the music, speeches, plays and prayers available to a generation who had never known how vibrant Somalia was prior to the war. But the attempt foundered with less than a third of the 225,000 items digitised.

Digitising the material is a cumbersome and expensive process. It involves using reel-to-reel digital converters – essentially tape audio output inputted into a recording computer – with some large tapes taking three hours to run.

Currently, with just one working digital converter, the shortage of these items is a major stumbling block. Added to this, using a converter is extremely labour-intensive. Technicians have to load, thread and play tapes that are already fragile and deteriorating onto antiquated converters which are prone to breaking down.

UN support

Working with the MoICT, the United Nations in Somalia has been exploring options for a solution to the urgent digitisation needs of Radio Mogadishu’s archives.

“The open-reel tape collection of Radio Mogadishu is a cultural treasure that all Somalis would benefit from,” says the Chief of the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia’s (UNSOM) Human Rights and Protection Group, Kirsten Young.

“Radio continues to play an important role in access to information in Somalia and having access to these rich archives would bring recent history into the homes of many Somalis,” adds Ms. Young, who also serves as the Representative of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to Somalia.

The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched the ‘Memory of the World (MoW) Programme’ in 1992 to protect against collective amnesia and to call for the preservation of the valuable archive holdings and library collections all over the world, to ensure their wide dissemination.

Digitisation of documentary heritage is an essential pillar for achieving the aim of the MoW Programme.

“After 30 years of conflict, and the almost total destruction or loss of the cultural records and artifacts of the Somali people, the preservation and digitisation of the Radio Mogadishu archive almost compels a response from development and implementing partners interested in the Somali people benefiting from and having access to and enjoyment of their own culture and heritage,” says the Head of UNESCO’s Somalia Desk, Mark Wall.

“The UNESCO ‘Memory of the World Programme,’ which aims to prevent the forgetting of the past, is an excellent stepping-off place for our subsequent moves in preserving the Radio Mogadishu archive for us all.

“We are keen on creating a programme to collect, document and encourage oral history inscriptions to the Memory of the World register – noting the current lack of audiovisual inscriptions – and hope that a recent joint proposal by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), OHCHR and UNESCO is compelling enough to mobilise funding for the Radio Mogadishu archive project to save, for humanity, the only significant surviving record of life in Somalia before the civil war,” he adds.

Source: UNSOM